Person.

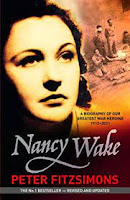

Nancy Wake (1912-2011) was always a restless kiwi, never content with being told no. As a child, she moved with her family from a Wellington suburb to Sydney Australia. At the age of 16, she ran away from home, first to New York City, and then to London, where she became a journalist. Landing a job with Hearst newspapers, she moved to Paris in the 1930s and traveled around Europe documenting the rise of the Nazis. In 1939, she married a wealthy French industrialist, and they lived in Marseilles.

When Germany invaded, she volunteered as an ambulance driver. After the creation of collaboration government Vichy France, she got involved with helping downed Allied pilots avoid capture and return to their bases. She herself got to be so adept at avoiding capture, the Gestapo called her the "White Mouse."

In 1943, she had to use the escape route herself, crossing the Pyrenees to neutral Spain and then heading to London. In London, she had advanced training and joined the SOE, Special Operations Executive. After parachuting back into central France with two other agents, she became a leader of the French Resistance Underground, the Maquis, and she continued to harass German troops through the end of the war.

Place.

In May and June of 1944, the largest gathering of French Resistance fighters, including Nancy Wake, took place at Mount Mouchet. In total, 7,000 fighters were divided into three groups, intending to launch a major attack on German forces. Instead, the Germans forced the fighters to flee after suffering heavy casualties.

In May and June of 1944, the largest gathering of French Resistance fighters, including Nancy Wake, took place at Mount Mouchet. In total, 7,000 fighters were divided into three groups, intending to launch a major attack on German forces. Instead, the Germans forced the fighters to flee after suffering heavy casualties.

Thing.

During the battle of and retreat from Mount Mouchet, Nancy Wake's unit list their radio, like these pictured, depriving them of necessary contact with London. Wake and a companion took bicycles and pedaled 310 miles round trip in 72 hours to find the nearest radio and operator in order to apprise London of their situation.

Person.

Many First Ladies are remarkable and important in some way. While some have been seen as fashion plates or crutches for their presidential husbands, others have been behind-the-scenes partners, sounding boards, protectors, and confidantes, but it's hard to argue the proposition that Eleanor Roosevelt (1884-1962) is in a class by herself.

The niece of Theodore Roosevelt, she lost her parents and a brother at a young age. Marriage to her fifth cousin , Franklin, did nothing to ease her life. His mother was the ultimate Smother, and he was definitely a Mama's boy. Then, she discovered his affairs. Unable and/or unwilling to leave him, which was practically unthinkable at the time, she resolved to create her own separate public life, also daring and unheard of, and reshaped the role of First Lady forever

As First Lady, she actually voiced opinions, even unpopular opinions like those favoring civil rights for all Americans. While Franklin dithered and dawdled and always put politics first, she became his eyes, ears, and legs, traveling the country, interacting with real people, doing what she could to improve things, and reporting to him. Unfortunately, he was too disinterested or or racist or cowardly or political to actually do something with what she reported most of the time. After leaving the White House, she continued to be a major force. Interesting alternate history scenario, imagine how things would have been different if she could have been president.

No Ordinary Time is an extraordinary book, as one would expect from Doris Kearns Goodwin, about their marriage and the World War Two years.

The niece of Theodore Roosevelt, she lost her parents and a brother at a young age. Marriage to her fifth cousin , Franklin, did nothing to ease her life. His mother was the ultimate Smother, and he was definitely a Mama's boy. Then, she discovered his affairs. Unable and/or unwilling to leave him, which was practically unthinkable at the time, she resolved to create her own separate public life, also daring and unheard of, and reshaped the role of First Lady forever

As First Lady, she actually voiced opinions, even unpopular opinions like those favoring civil rights for all Americans. While Franklin dithered and dawdled and always put politics first, she became his eyes, ears, and legs, traveling the country, interacting with real people, doing what she could to improve things, and reporting to him. Unfortunately, he was too disinterested or or racist or cowardly or political to actually do something with what she reported most of the time. After leaving the White House, she continued to be a major force. Interesting alternate history scenario, imagine how things would have been different if she could have been president.

No Ordinary Time is an extraordinary book, as one would expect from Doris Kearns Goodwin, about their marriage and the World War Two years.

Place.

Val-Kill is a National Park Service-managed site located about two miles from the Franklin Roosevelt Home in Hyde Park New York. There are two main buildings, one a small cottage, and the other a larger building used as a handicrafts and artisans factory.

While the Roosevelts used the smaller estate for more intimate entertaining on occasion, FDR suggested that that Eleanor use the factory building as a workshop to fulfill her interest in developing local artists and craftsmen, especially women. (One might also suspect that there was another reason he urged her to be elsewhere.)

After FDR's death, the factory was converted into a home, and Eleanor lived in it until her death.

While the Roosevelts used the smaller estate for more intimate entertaining on occasion, FDR suggested that that Eleanor use the factory building as a workshop to fulfill her interest in developing local artists and craftsmen, especially women. (One might also suspect that there was another reason he urged her to be elsewhere.)

After FDR's death, the factory was converted into a home, and Eleanor lived in it until her death.

Thing.

Historians don't always find diaries, journals, and letters written by their subjects. Sometimes, it's just a few pieces of ephemera, documents, shopping lists, receipts, bills etc. All of these things can contribute to the storytelling. Personally, I find the gun license most interesting.

It's the same for family histories. As in my case, I don't have much in the way of written materials of my grandparents and parents, maybe just a driver's license, and a couple of other things, but they're important to me.

History is not just the major events, maybe more often than not, history is the mundane.

It's the same for family histories. As in my case, I don't have much in the way of written materials of my grandparents and parents, maybe just a driver's license, and a couple of other things, but they're important to me.

History is not just the major events, maybe more often than not, history is the mundane.

Person.

.I always love finding great books about things and people I never knew. This is definitely one of those. I just happened to be in the car at the right time to hear an interview with Stephen L. Carter, the author of the biography of his grandmother, Invisible: The Forgotten Story of the Black Woman Lawyer Who Took Down America's Most Powerful Mobster. (See blog about his books here

https://thehistocratsbookshelf.blogspot.com/2020/11/author-spotlight-stephen-l-carter.html?m=1 )

The book research was a revelation to him as well. He talked about how his grandmother was a stern, somewhat distant figure in his childhood, and he learned so much about her.

Eunice Carter was born in Atlanta in 1899. Her father was a founder of the black division of the YMCA, her mother was a social worker. Her grandfather had purchased his freedom before the Civil War. Eunice earned a degree in social work and then decided to become a lawyer.

She became one of New York City's first black female attorneys and one of the first prosecutors of color in the country. In 1935, she became the first black woman assistant DA in New York State, and she was assigned to a task force to bring down the biggest mobster at the time. Lucky Luciano. She did. Later, she became highly involved in the Republican Party and the United Nations. More than one contemporary said of her, "If she had been a man, she could have been president."

It's a great story, and I've enjoyed Carter's novels as well.

https://thehistocratsbookshelf.blogspot.com/2020/11/author-spotlight-stephen-l-carter.html?m=1 )

The book research was a revelation to him as well. He talked about how his grandmother was a stern, somewhat distant figure in his childhood, and he learned so much about her.

Eunice Carter was born in Atlanta in 1899. Her father was a founder of the black division of the YMCA, her mother was a social worker. Her grandfather had purchased his freedom before the Civil War. Eunice earned a degree in social work and then decided to become a lawyer.

She became one of New York City's first black female attorneys and one of the first prosecutors of color in the country. In 1935, she became the first black woman assistant DA in New York State, and she was assigned to a task force to bring down the biggest mobster at the time. Lucky Luciano. She did. Later, she became highly involved in the Republican Party and the United Nations. More than one contemporary said of her, "If she had been a man, she could have been president."

It's a great story, and I've enjoyed Carter's novels as well.

Place.

The first YMCA was founded in London by Sir George Williams and 11 friends. Seven years later, Thomas Sullivan introduced the Y into the US in Boston in 1851. The Ys were founded to serve as a refuge for young men, initially sailors who found themselves in strange cities, and provide a wholesome place for body and soul.

Since most Ys were white-only in the US, Anthony Bowen founded the first black Y in 1853 in Washington DC. In 1875, Eunice Carter's father, William A. Hunton, became the first full-time, paid director of a black YMCA in Norfolk Virginia. In 1890, the national Y created a "Colored Men's Department," and appointed Hunton as its first secretary.

The black YMCAs provided "educational and spiritual oases" for young black men, secure places to discuss and debate, as well as make use of libraries, pools, and gyms. Black YMCAs often became community centers in black communities.

Since most Ys were white-only in the US, Anthony Bowen founded the first black Y in 1853 in Washington DC. In 1875, Eunice Carter's father, William A. Hunton, became the first full-time, paid director of a black YMCA in Norfolk Virginia. In 1890, the national Y created a "Colored Men's Department," and appointed Hunton as its first secretary.

The black YMCAs provided "educational and spiritual oases" for young black men, secure places to discuss and debate, as well as make use of libraries, pools, and gyms. Black YMCAs often became community centers in black communities.

Thing.

The mugshot of Lucky Luciano.

Charles "Lucky" Luciano ( 1897 – 1962) was an Italian-born mobster who operated mainly in the United States. Luciano started his criminal career in the Five Points Gang and is considered the father of modern organized crime in the US for the establishment of The Commission in 1931. He was also the first official boss of the modern Genovese crime family.

In 1936, he was tried and convicted for compulsory prostitution and running a prostitution racket after years of investigation led by Assistant DA Eunice Carter. He was sentenced to 30 to 50 years in prison, but during WWII, an agreement was struck with the Department of the Navy to provide naval intelligence. In 1946, for his alleged wartime cooperation, his sentence was commuted on the condition that he be deported to Italy. Luciano died in Italy on January 26, 1962, and his body was permitted to be transported back to the United States for burial.

Charles "Lucky" Luciano ( 1897 – 1962) was an Italian-born mobster who operated mainly in the United States. Luciano started his criminal career in the Five Points Gang and is considered the father of modern organized crime in the US for the establishment of The Commission in 1931. He was also the first official boss of the modern Genovese crime family.

In 1936, he was tried and convicted for compulsory prostitution and running a prostitution racket after years of investigation led by Assistant DA Eunice Carter. He was sentenced to 30 to 50 years in prison, but during WWII, an agreement was struck with the Department of the Navy to provide naval intelligence. In 1946, for his alleged wartime cooperation, his sentence was commuted on the condition that he be deported to Italy. Luciano died in Italy on January 26, 1962, and his body was permitted to be transported back to the United States for burial.

Person.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl was an important autobiographical slave narrative written by Harriet Jacobs, an enslaved woman born in Edenton North Carolina in 1813. (Died 1897)

When she was a child, she was taught to read and write by her mistress, which was highly unusual (but not yet explicitly illegal in all slave states, it was generally made illegal after Nat Turner's rebellion in 1831), but at 12, she became the property of an abusive owner who sexually assaulted her. In her teens, she bore two children fathered by another white man. Her jealous owner threatened to sell her children, and she went into hiding for seven years in the attic space of her grandmother's, a freed woman, house. Meanwhile, the father of her children bought them and put them in her grandmother's care.

Harriet finally escaped to New York in 1842. She and her brother, who had also escaped separately, got involved with William Lloyd Garrison and other noted abolitionists, and she started writing her story in 1853. She wrote the story under a pseudonym and changed all of the names. In 1860, a publisher put her in touch with Lydia Child who acted as her editor and wrote the introduction when the book was published in 1861.

During the Civil War, she became a nurse in Washington DC. Along with her daughter, she traveled south with Union troops, working in Savannah Georgia in 1865. She remained in Savannah for a few years working with orphans and refugees. She spent her last years in Cambridge Massachusetts and Washington DC.

Incidents was the first, if not the only, abolitionist book that focused primarily on sexual oppression and abuse and the horrors of slavery as they fell especially on enslaved mother's and their children. It was a landmark work in abolitionist literature, but, by the 20th century, it had fallen out of print and was little known. Incidents began to be "rediscovered" in the 1960s, influencing many historians and authors like Colson Whitehead (The Underground Railroad).

When she was a child, she was taught to read and write by her mistress, which was highly unusual (but not yet explicitly illegal in all slave states, it was generally made illegal after Nat Turner's rebellion in 1831), but at 12, she became the property of an abusive owner who sexually assaulted her. In her teens, she bore two children fathered by another white man. Her jealous owner threatened to sell her children, and she went into hiding for seven years in the attic space of her grandmother's, a freed woman, house. Meanwhile, the father of her children bought them and put them in her grandmother's care.

Harriet finally escaped to New York in 1842. She and her brother, who had also escaped separately, got involved with William Lloyd Garrison and other noted abolitionists, and she started writing her story in 1853. She wrote the story under a pseudonym and changed all of the names. In 1860, a publisher put her in touch with Lydia Child who acted as her editor and wrote the introduction when the book was published in 1861.

During the Civil War, she became a nurse in Washington DC. Along with her daughter, she traveled south with Union troops, working in Savannah Georgia in 1865. She remained in Savannah for a few years working with orphans and refugees. She spent her last years in Cambridge Massachusetts and Washington DC.

Incidents was the first, if not the only, abolitionist book that focused primarily on sexual oppression and abuse and the horrors of slavery as they fell especially on enslaved mother's and their children. It was a landmark work in abolitionist literature, but, by the 20th century, it had fallen out of print and was little known. Incidents began to be "rediscovered" in the 1960s, influencing many historians and authors like Colson Whitehead (The Underground Railroad).

Place.

For 7 years before her escape to New York, Harriet Jacobs used the small attic crawlspace or garret of her freed grandmother's house. The space was nine feet long, seven feet wide, and three feet at its tallest.

Within black feminist thought, the garret has become a powerful metaphor, notably due to the work of Katherine McKittrick, who points out the garret space ironically represented both confinement and freedom in Jacobs' life.

Within black feminist thought, the garret has become a powerful metaphor, notably due to the work of Katherine McKittrick, who points out the garret space ironically represented both confinement and freedom in Jacobs' life.

Thing.

After doing some nursing during the Civil War, Harriet Jacobs and her daughter Louisa answered the call of the New England Freedmen's Aid Society, made in this flyer, urging men and women to go South in order to open and operate schools for the freed slaves. The Jacobs ladies moved to Savannah in 1865 and opened a school, living in Savannah for a couple of years.

Across the South, hundreds of volunteers, men and women, black and white, some Union veterans, opened schools in barns, churches, homes, or wherever they could. The schools were crowded with former slaves from ages five to 95, eager to learn to read and write. These schools were operated under the auspices of charities and missionary societies like the New England Freedmen's Aid Society. When the Freedmen's Bureau was created by Congress, it took over the task of education, one of the most successful of its programs.

Across the South, hundreds of volunteers, men and women, black and white, some Union veterans, opened schools in barns, churches, homes, or wherever they could. The schools were crowded with former slaves from ages five to 95, eager to learn to read and write. These schools were operated under the auspices of charities and missionary societies like the New England Freedmen's Aid Society. When the Freedmen's Bureau was created by Congress, it took over the task of education, one of the most successful of its programs.

Person.

Captain Cook's "discovery" of the Hawaiian Islands marked the beginning of an end of Hawaiian culture. He was soon followed by whalers who made Hawaii a rest/sex stop, then Christian missionaries intent on saving the "heathens," and finally American planters and companies like Dole that realized Hawaii was perfect for pineapple and sugar cane cultivation, and the land and labor were free for the taking. After all, the Hawaiians we're just simple, uncivilized little brown people

The Hawaiian Islands were unified in the late 1700s by King Kamehameha I, after a long period of civil war. Lili'uokalani (1838-1917), called "Queen Lil" by the Americans, ascended to the throne following her brother's death in 1891. Previous rulers had been bribed, coerced, and threatened into writing a constitution that face great power to the American planters. As queen, Lili'uokalani immediately began work on a new Constitution protecting her people and her country.

Of course, the planters couldn't allow that to happen, so, led by Sanford Dole, they fired off a telegram to President Harrison which said that Queen Lil was threatening American lives and property. Harrison sent a unit of marines, Queen Lili'uokalani's government was overthrown, and Dole became the President of the first Republic of Hawaii, and he immediately sought US annexation. President Harrison and his successor, Grover Cleveland realized that the planters had lied and refused annexation, which was completed by McKinley in 1898.

Following a brief counterrevolution in 1895, Lili'uokalani officially abdicated her throne in return for the promise to free the imprisoned conspirators. She was tried for treason to the Republic and sentenced to give years hard labor. That sentence was commuted to house arrest in her palace until she was pardoned in October 1896.

Unfamiliar Fishes by Sarah Vowell is a good history of Hawaii. While she is not an historian, I love Vowell's wit and insight. She tells great stories.

The Hawaiian Islands were unified in the late 1700s by King Kamehameha I, after a long period of civil war. Lili'uokalani (1838-1917), called "Queen Lil" by the Americans, ascended to the throne following her brother's death in 1891. Previous rulers had been bribed, coerced, and threatened into writing a constitution that face great power to the American planters. As queen, Lili'uokalani immediately began work on a new Constitution protecting her people and her country.

Of course, the planters couldn't allow that to happen, so, led by Sanford Dole, they fired off a telegram to President Harrison which said that Queen Lil was threatening American lives and property. Harrison sent a unit of marines, Queen Lili'uokalani's government was overthrown, and Dole became the President of the first Republic of Hawaii, and he immediately sought US annexation. President Harrison and his successor, Grover Cleveland realized that the planters had lied and refused annexation, which was completed by McKinley in 1898.

Following a brief counterrevolution in 1895, Lili'uokalani officially abdicated her throne in return for the promise to free the imprisoned conspirators. She was tried for treason to the Republic and sentenced to give years hard labor. That sentence was commuted to house arrest in her palace until she was pardoned in October 1896.

Unfamiliar Fishes by Sarah Vowell is a good history of Hawaii. While she is not an historian, I love Vowell's wit and insight. She tells great stories.

Place.

Iolani Palace, completed in 1882, is the only royal Palace in the United States. It was the home of the Hawaiian monarchy, and Queen Lili'uokalani was kept under house arrest here following her overthrow.

Its construction cost $340,000 then equivalent to about 9.5 million dollars today.

Its construction cost $340,000 then equivalent to about 9.5 million dollars today.

Thing.

Hawaiian royalty and nobles wore elaborate feather cloaks and capes. Each consists of thousands of feathers and required thousands of hours to create. They were passed down for generations and given as gifts to heads of state.

They are important to biologists as well as historians because many of them contain feathers of endangered or extinct birds.

They are important to biologists as well as historians because many of them contain feathers of endangered or extinct birds.

Person.

On March 25, 1911, a fire broke out and swept through the Triangle Shirtwaist (woman's blouse) Company which occupied the 8th, 9th, and 10th floors of the Asch Building, near Washington Square Park, New York City. The building lacked many fire safety features, and the few fire escapes buckled immediately. Escape paths were blocked by carts, machines, and piles of flammable fabric and clothing, and the exit doors were locked from the outside --- not an uncommon practice at the time to limit unauthorized breaks. The NYC Fire Department was not prepared, training- or equipment-wise. Most of the workers were young immigrant women ages 14-23, and factory work at the Triangle was one of the few options open to them. When it was over, 146 were dead, 123 women. Many had been forced to jump to their deaths from windows.

The owners of the building were tried and acquitted for manslaughter. In a civil trial, they were found liable and ordered to pay families $75 per victim. (Their insurance company paid the owners $400 per victim.) The owners were fined $20, total, for locking the exit doors. The disaster galvanized public opinion and strengthened the hand labor unions in the city. Numerous fire safety and labor regulations were enacted, and improvements in firefighter training and equipment were made.

As a result of the fire, Frances Perkins (1880-1965), rose to state prominence. She had already been an active suffragist and advocate of women's and workers' rights for years, but, after the fire, she became Executive Secretary of the NYC Committee on Safety, overseeing reforms. She went on to hold several state government positions over the next two decades.

In 1933, FDR nominated her as Secretary of Labor, and she became the first woman Cabinet member, and the longest-serving (12 years). After the Cabinet, Truman appointed her to the US Civil Service Commission until 1952. From 1952 until her death at 85 in 1965, she was a lecturer at Cornell University.

Place.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Company was one of several garment companies in the Asch Building. Built in 1900-1901, the owner touted the building's "fireproof" rooms. Triangle occupied the 8th, 9th, and 10th floors. There were few working bathrooms. Spaces were overcrowded with machines, fabrics, shirtwaists, and people. There was no sprinkler system and one substandard fire escape. Staircases had no landings, and stairwells were poorly illuminated.

Today, the building belongs to New York University and is known as the Brown Building.

Today, the building belongs to New York University and is known as the Brown Building.

Thing.

So, what is a shirtwaist anyway? Around the turn of the century, America was in the midst of some major social changes. One of these changes involved women, mainly single women until they married, taking jobs outside of their homes: switchboard operators, department store clerks, secretaries and office assistants, and teachers. Shirtwaists became the fashion choice for young working women. They were buttoned ladies blouses, resembling mens' shirts that could be worn under a jacket or not, and tucked into a skirt.

Triangle is an excellent book, and is now free on Kindle Unlimited.

Triangle is an excellent book, and is now free on Kindle Unlimited.

Person.

Heaven's Bride is another one of those books about a subject that I and most Americans never hear about in history, Ida C. Craddock (1857-1902). Craddock was an American advocate of free speech and women's rights, which landed her in court often on obscenity charges in the late 1800s

Craddock was raised a Quaker in Philadelphia, and was recommended by faculty to be the first female undergraduate student admitted into the University of Pennsylvania, but her entrance was blocked by the Board of Trustees. In her thirties, she left Quakerism and became an occultist. In her writing, she tried to synthesize mystic literature from many cultures into a single whole. She became what was termed at the time a "freethinker," and she soon developed a particular interest in religious eroticism, a self-proclaimed Prophetess of the Church of Yoga. She claimed to be married to an angel named Soph. She claimed that her nightly lovemaking with Soph was so noisy that neighbors complained. Her mother unsuccessfully (surprisingly at the time) tried and failed to have her institutionalized.

Craddock was raised a Quaker in Philadelphia, and was recommended by faculty to be the first female undergraduate student admitted into the University of Pennsylvania, but her entrance was blocked by the Board of Trustees. In her thirties, she left Quakerism and became an occultist. In her writing, she tried to synthesize mystic literature from many cultures into a single whole. She became what was termed at the time a "freethinker," and she soon developed a particular interest in religious eroticism, a self-proclaimed Prophetess of the Church of Yoga. She claimed to be married to an angel named Soph. She claimed that her nightly lovemaking with Soph was so noisy that neighbors complained. Her mother unsuccessfully (surprisingly at the time) tried and failed to have her institutionalized.

She moved to Chicago and opened a practice offering "mystical" sexual counseling to married couples in person and through the mail. The last bit is what got her into federal trouble. At the time, free speech was throttled by the US Postal Inspector Anthony Comstock and the law against obscenity in the mail named after him, the Comstock Act. As America's self-appointed arbiter of obscenity, any reference to sex, even medical textbooks about sex, birth control, or reproduction, were deemed obscene. And he zeroed on Craddock's pamphlets and books sent through the mail.

Craddock was indicted, tried, and convicted in federal courts several times. In one case, the judge ruled that the pamphlet was so obscene that the jury could not even look at it. In 1902, she was given the choice of imprisonment or institutionalization. She chose suicide.

Place.

Ida Craddock attained national notoriety in 1893 during the "hoochie-coochie" controversy at the Columbian Exposition or the Chicago World's Fair. An entrepreneur named Sol Bloom had introduced Middle Eastern dance, or belly dancing, to America at the Egyptian, Turkish, and Algerian pavilions. He has seen the dance at the Paris World's Fair and saw a chance to make some money in Chicago. It was unknown in America before 1893 and went by several names: danse du ventre, oriental dance, hoochie-coochie, coochie, coochie, muscle dance, and belly dance. Immediately, there was a huge public uproar, led by the Exposition's Board of Lady Managers appointed to make sure that the attractions were suitable for ladies. The bare midriffs, gyrations, improvisational gestures, direct eye contact with audience members, and permanently fixed smiles were deemed obscene.

Ida Craddock wrote several nationally published editorials defending the dance and the dancers. Soon, commercial success overpowered moral outrage, and the dancers continued. In fact, belly dancing became very popular across the country, including in carnival sideshows, where hoochie-coochie dancers performed, often to male-only audiences.

Ida Craddock wrote several nationally published editorials defending the dance and the dancers. Soon, commercial success overpowered moral outrage, and the dancers continued. In fact, belly dancing became very popular across the country, including in carnival sideshows, where hoochie-coochie dancers performed, often to male-only audiences.

Thing.

"The Wedding Night" is the 24-page pamphlet written by Ida Craddock that generated her last clash with federal authorities, who prosecuted her for violating the Comstock Act against sending obscene materials through the mail. The pamphlet discusses sexual intercourse very directly and frankly, and it also advises young married partners that empathy and consideration for one's sexual partner are essential attributes in a marriage.

The pamphlet was deemed obscene, and she was given a choice: 5 years in federal prison or institutionalization. She refused to accept institutionalization, and the day before she was to report to federal prison, she committed suicide by slashing her wrists and turning on the gas in her oven.

No comments:

Post a Comment